10 Winter Masterpieces To Know

Introduction

Winter has always asked more of us—more imagination, more patience, more attention. Across continents and centuries, artists have turned toward the season not simply to record weather, but to understand themselves, using snow, shadow, and silence as a kind of emotional language.

In this curated guide, we travel through time and across seas to explore ten winter masterpieces that shaped how the world sees the cold months.

Think of this as a slow walk through a global gallery: a quiet docent at your side, a blend of warmth and scholarship, and a steady invitation to look closer. These artworks aren’t merely scenes of winter; they are reflections of history, belief, beauty, survival, and the ways humans interpret the cold.

Welcome in. Here are the ten winter masterpieces that shaped how the world sees the season:

1. Hunters in the Snow (1565)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Flanders / Belgium)

Why it’s famous:

The first great winter landscape in Western art. Bruegel wasn’t depicting weather—he was depicting humanity inside winter, shaping how Europe imagined the season for centuries. It’s also part of Bruegel’s “Labours of the Months” cycle, a rare Renaissance series showing everyday life across a full year.

Medium: Oil on wood panel

Dimensions: 117 × 162 cm / 46.1 × 63.8 in

See it in person: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Image Source: Smart History

2. Winter Landscape (1811)

Caspar David Friedrich (Germany)

Why it’s famous:

A cornerstone of German Romanticism. Winter becomes spiritual metaphor—a quiet journey toward hope. This painting defined the “solitary figure in vast nature” motif and shaped how artists used landscape to express inner states rather than scenery alone.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 32.5 × 45 cm / 12.8 × 17.7 in

See it in person: The National Gallery, London

Image Source: The National Gallery

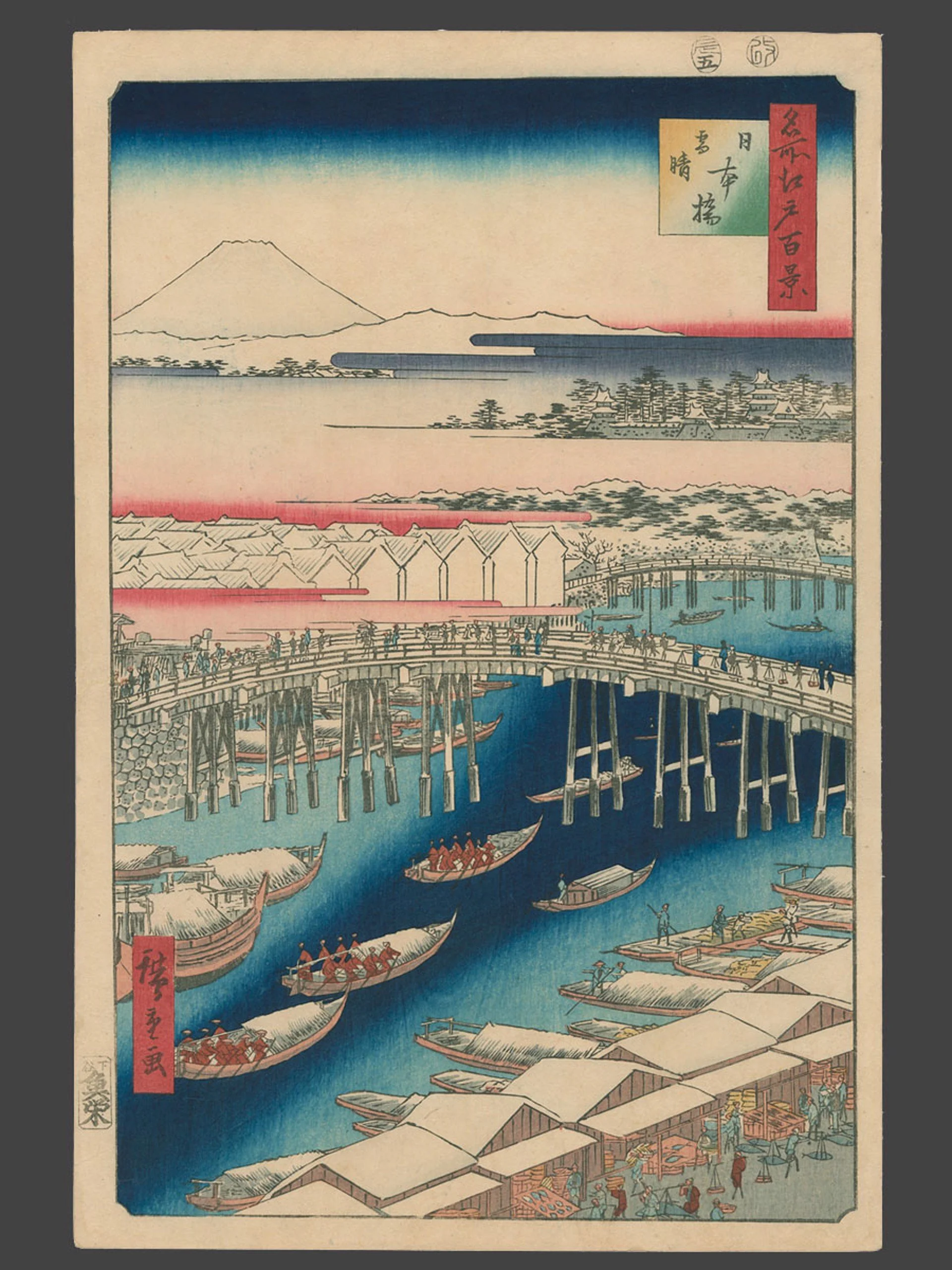

3. 日本橋 雪晴 — Nihonbashi: Clearing After Snow (1833–34)

歌川広重 Utagawa Hiroshige (Japan)

Why it’s famous:

One of Hiroshige’s most celebrated winter scenes. Snow becomes rhythm—a pattern of quiet falling across Edo. This print influenced Monet, Whistler, and Van Gogh, helping shape global Impressionism and cementing the “ukiyo-e winter morning” visual archetype.

Medium: Polychrome woodblock print

Dimensions: 36 × 24.5 cm / 14.2 × 9.6 in

See it in person: The Met (NYC), MFA Boston, British Museum (London)

Image Source: The Art of Japan

4. The Magpie (1868–69)

Claude Monet (France)

Why it’s famous:

One of Monet’s most beloved works. A study of how light moves across snow—subtle blues, violets, and warm shadows. Rejected by the Salon when first shown, it’s now considered a turning point in Monet’s lifelong exploration of atmospheric light.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 89 × 130 cm / 35 × 51.2 in

See it in person: Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Image Source: The Conversation

5. Snow at Montfoucault (1874–75)

Camille Pissarro (France)

Why it’s famous:

The most human winter in Impressionism. Pissarro paints winter not as spectacle but as everyday life—muddy roads, low buildings, quiet labor. Its restrained palette reflects Pissarro’s role as the movement’s moral center.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 61 × 74 cm / 24 × 29 in

See it in person: The Art Institute of Chicago

Image Source: The Fitzwilliam Museum

6. Зимний пейзаж — Winter Landscape (1909)

Василий Кандинский Wassily Kandinsky (Russia)

Why it’s famous:

Painted during Kandinsky’s shift toward abstraction. Winter becomes emotion through color—a bridge between realism and modernism. Works like this mark his transition toward the pure abstraction that would define 20th-century art.

Medium: Oil on cardboard

Dimensions: 75.5 × 97.5 cm / 29.7 × 38.4 in

See it in person: Lenbachhaus Museum, Munich

Image Source: The Conversation

7. The Fox Hunt (1893)

Winslow Homer (United States)

Why it’s famous:

One of America’s great winter masterpieces. Homer turns winter into narrative; the viewer becomes witness, not just observer. The diagonal sweep of the fox across the snow is one of the most studied American compositions, symbolizing nature’s indifference and the fragility of survival.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 96.5 × 174 cm / 38 × 68.5 in

See it in person: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Image Source: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

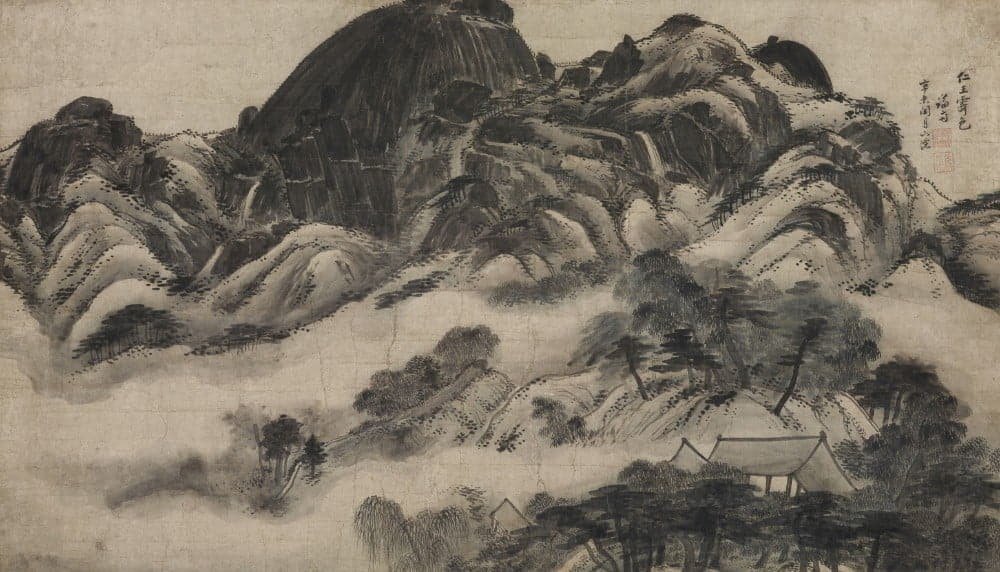

8. 인왕제색도 — Inwang Jesaekdo (1751)

정선 Jeong Seon (Korea)

Why it’s famous:

The most iconic landscape in Korean art history. Jeong Seon captured Mount Inwang after a rainstorm using ink wash to express shifting mist, cold air, and the raw energy of nature. This work broke from Chinese models and defined the uniquely Korean “true-view” style.

Medium: Ink and wash on paper

Dimensions: 79.2 × 138.2 cm / 31.2 × 54.4 in

See it in person: National Museum of Korea, Seoul

Image Source: Visit Seoul

9. Death (1898–99)

By Giovanni Segantini (Italy/Switzerland)

Why it’s famous:

A haunting panel from Segantini’s Alpine Triptych. Painted high in the Engadine Valley, it turns winter into metaphor—soft sky, luminous snow, and tiny human figures dwarfed by mountains. Segantini died before the triptych was completed, giving the work a sense of inevitability and legacy.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 191.5 × 323 cm / 75.4 × 127.2 in

See it in person: Segantini Museum, St. Moritz

Image Source: Segantini Museum

10. March (1895)

by Isaac Levitan (Russia)

Why it’s famous:

One of the most beloved winter landscapes in Russian art. Levitan captures the exact moment winter loosens—sunlight warming snow, shadows shifting, a sense of quiet renewal. The work exemplifies the Russian “lyrical landscape” tradition, where emotion and nature merge without overt symbolism. It remains one of the Tretyakov Gallery’s most iconic paintings.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 60 × 75 cm / 23.6 × 29.5 in

See it in person: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Image Source: Tretyakov Gallery Magazine

Conclusion

Winter reveals things other seasons hide. It pares a landscape down to its essentials—line, light, breath, survival—and artists around the world have long understood its power.

From Edo’s crisp mornings to the Alps’ blue hush, from Korean ink mist to America’s sharpened narrative tension, these works remind us that winter is not a blank season but a deeply expressive one.

May these ten masterpieces slow your gaze, expand your sense of the season, and offer a moment of stillness in the rush of the year. Wherever you are, consider this your museum moment—no ticket required.